Taxi Cab Medallions, Uber, and The Transitional Gains Trap: Part 1

As Ed Lopez suggested in this post back in December 2012, the political battles surrounding the emergence of Uber and other ride-share services have proven to be a goldmine for those of us studying and teaching political economy, with the taxi cab medallion at the center of this story of political change. Both the introduction of the taxi cab medallion and the more recent political struggle in reaction to the entry of ride-share service firms provide for excellent applications of the story of political change as described in Madmen.

In this post I discuss the forces of political change that led to the establishment of the taxi medallion system in New York City in 1937. Part 2 of this discussion, which I will post later this week, will discuss how the medallion system, with the resulting vested interests, has led to a transitional gains trap and to the political barriers being enacted against Uber and other ride-share services.

The Introduction of the Taxi Cab Medallion:

In the early 1930’s, the tax cab environment was ripe for government intervention. As is described briefly in this PBS historical story of the taxi, public sentiment against the existing taxi industry was growing–both among the cabbies and the public at large. High unemployment of the Great Depression led to an increased supply of cabbies, allowing working conditions to worsen (i.e., longer hours and lower wages). Discontent among New York City cabbies came to a head in 1934 when more than 2,000 cabbies organized a strike in Times Square.

General public angst with the taxi industry was also coming to a head in the early 1930’s, as claims of price gauging grew more frequent as did complaints concerning the ethics and morality of the business. During prohibition, cabbies learned that speakeasies, and not hotels, provided the best opportunity for larger tips; they predictably frequented such areas more often. Further, safety concerns grew as cabbies worked longer shifts and maintenance became infrequent in an effort to retain positive cash flow despite increased competition and reduced passengers during the depression.

With the stock market crash and the general status of the economy, the public’s trust in the market had also been shaken. Thus, rather than rely on private sector solutions to their concerns, both consumers and cabbies were likely more confident with solutions proposed public officials than they had been prior to the crash.

With both the general public and the cabbies vocalizing their displeasure and the growing general sentiment against unregulated markets, the environment was set for local politicians and powerful special interests to enact change. The special interests of concern were primarily theowners of the largest taxi fleets, namely Checker Cab Company, General Motors, and Ford Motor Company, among others.

Consideration of authorizing a monopoly for taxi services in NY City were squashed with the reports of the Checker Cab Company bribing then Mayor Walker (here and here). The tax cab medallion, signed into law by Mayor La Guardia with the Haas Act of 1937, brought all the key parties together. The public was assured of increased safety and were promised reasonable, standardized fares. The cabbies secured reduced hours and acceptable compensation through required licensing to drive a taxi.

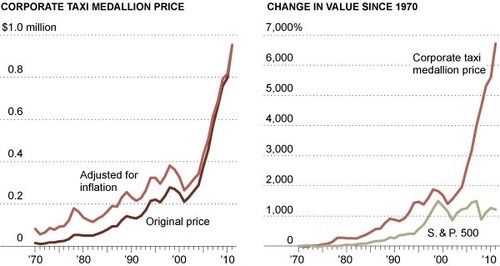

The primary beneficiaries of the medallion system were–and still are–the limited number of large fleet owners who owned the medallions and leased their taxi (roughly 70% of the 11,787 taxi medallions at the time according to Wikipedia). The resale value of taxicab medallions in NY City in May of this year exceeded $1 million (here) and the growth of value of medallions across many major cities has outpaced that of the S&P500 by a large margin over the past 40 years (source for charts):

Those currently holding such high priced medallions will resist any change that puts that value at risk despite the propensity of the change to benefit society at large–it is what Gordon Tullock has famously coined a transitional gains trap. In Part 2 of this series to be posted later this week, I will discuss this transitional gains trap as it relates to on-going policy restricting ride-share services.

One thought on “Taxi Cab Medallions, Uber, and The Transitional Gains Trap: Part 1”

Comments are closed.