Ranking Think Tanks: The Measurement Problem

In an initial post last week, I argued that the proliferation of think tanks over the past 50 years is likely to be a good influence on human affairs, and so is the emerging competition to measure (rank) the performance of think tanks. In this follow-up post and a planned third, I will question the usefulness of the measures used in these rankings.

Why measure think tank effectiveness with data like social network impact, web traffic, publication counts, and academic citations? Well, like the man who looks for his lost keys under the street lamp where the light is good, the answer is: because these are the best, easily available data.

Yet the ultimate measures of a think tank’s success are more complex and obscured, for three sets of interrelated reasons.

1). The ultimate goal of a think tanks is not merely to influence the climate of ideas and public opinion, but to change social institutions in the direction of its guiding philosophies. Web traffic, publication counts, and so forth aren’t capturing outcomes, but instead are capturing proxies that can be related to outcomes but clearly are one or more steps removed.

Ideally a think tank’s performance would be measured by its marginal effect on the power of ideas to overcome interests that defend a status quo. What are the marginal effects of a think tank on the evolution of public opinion, where madmen in authority make their appeal? What are its marginal effects on the set of proposals that are “politically feasible” at any time and place? And what are its marginal effects on the set of proposals that ultimately are adopted? Answers to these would capture truer measures of a think tank’s effectiveness because these would capture its unique contributions to political change.

It is not difficult to conceive of such measurements, but executing them would be both costly and imperfect. And this is one reason why (for now) it still makes sense to use proxies.

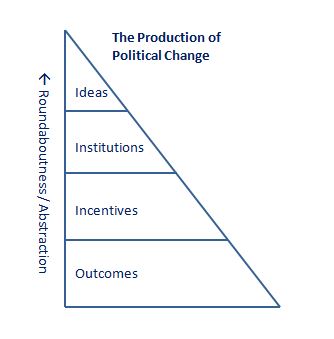

2). Long and uncertain periods of time separate a think tank’s everyday activities from the eventual, ultimate outcomes that it seeks to influence. The framework in Madmen identifies the stages of production that generate political change.

Outcomes in society are the summation of individual actions that are guided by incentives. In turn, incentives are shaped by institutions, and institutions are shaped by the flow of ideas doing battle with status quo interests. It is in this top segment of the triangle where think tanks compete – in the marketplace of ideas. To put it slightly differently, a think tank’s business model is one of investment in ideas, and the returns to investment materialize as institutional change over long and uncertain periods of time.

How might we measure and rank the efforts of think tanks today in terms of their payoff in the future? For example, London’s Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) toiled for two decades before Margaret Thatcher rose to power and began sourcing from IEA many of her proposals for change (HT: Brad DeVos). It would require some clever measures to have IEA ranked highly during its first 20 years. Again, those measures would be costly and imperfect.

3). Unlike market competition, political and intellectual entrepreneurs lack the discipline of clear success and failure metrics. What are a think tank’s deliverables? How does it demonstrate its rate of return to its investors/donors? This is not as straightforward as a corporation referring stockholders to its profit & loss statement, or even a newspaper showing advertisers its circulation numbers. A market entrepreneur is guided by relatively clear feedback mechanisms—profit and loss denominated in units of the currency. By comparison, a political or intellectual entrepreneur is guided by more nuanced, even murkier criteria.*

These interrelated reasons might be sufficient to argue that measuring think tank effectiveness is difficult, and perhaps prohibitively so. But data and measurement techniques could (and probably will) get better. And the framework above could lead to specific theories and testable hypotheses that improve our understanding of long-term investment in ideas. Till then, it will still make sense to use proxies instead of truer measures of effectiveness—i.e. to look for our keys under the street lamp, where the light is good.

For the onlooker (e.g., the analyst seeking to measure performance), this means the performance picture is relatively bright in market competition, but relatively dim in political and intellectual competition. For the think tank, this means having to consider carefully its various strategies, and having to take different sorts of risks compared to market entrepreneurs. This will be the starting point of the third post in this series.

—

*Note: I raise the issue of market vs. political entrepreneurs’ feedback mechanisms on Marginal Revolution, and Wayne elaborates in his entry “Learning From Failure” here on PE.

Update: Corrected for typo. Here is a link to the next (third) entry in this series, “Ranking Think Tanks: The Challenge of Specialization“

2 thoughts on “Ranking Think Tanks: The Measurement Problem”

Comments are closed.